Superheterodyne Receiver: Difference between revisions

| Line 25: | Line 25: | ||

[http://findingaids.cul.columbia.edu/ead/nnc-rb/ldpd_4078687/summary Edwin H. Armstrong Papers] </p> | [http://findingaids.cul.columbia.edu/ead/nnc-rb/ldpd_4078687/summary Edwin H. Armstrong Papers] </p> | ||

Walter Schottky, [www.nonstopsystems.com/radio/article-superhet.pdf "On the Origin of the Super-Heterodyne Method," Proceedings of the I.R.E. 14 (Oct. 1926)] </p> | Walter Schottky, [http://www.nonstopsystems.com/radio/article-superhet.pdf "On the Origin of the Super-Heterodyne Method," Proceedings of the I.R.E. 14 (Oct. 1926)] </p> | ||

[[Category:Communications]] | [[Category:Communications]] | ||

Revision as of 21:25, 18 April 2012

Superheterodyne Receiver

In radio broadcasting, a transmitting antenna sends out electromagnetic waves that carry the radio program. A radio antenna may pick up these electromagnetic waves. The free electrons in the metal antenna are jostled back and forth by the passing radio wave. Converting the tiny currents created by this jostling into the speech or music of the radio program is the job of a radio receiver.

There are many different ways a radio receiver can perform this conversion. Reginald Fessenden was the first to apply one of these methods, called the heterodyne principle, to wireless communications in 1901. Fessenden coined the term heterodyne from the Greek words for "other" and "force." The heterodyne principle is based on a well-known sound phenomenon where the combination of two audio tones with frequencies A and B results in an oscillation equal to frequency A minus B. This phenomenon is exploited in the tuning of pianos.

Fessenden suggested that the heterodyne principle be employed in a radio receiver by mixing the incoming radio wave with a locally generated wave of slightly different frequency. The combined wave then drives the diaphragm of an earpiece at the frequency of the audio. For example, mixing a 101 kHz input with a 100 kHz signal generated by the receiver yields a frequency of 1 kHz, which is in the audible range. Lacking an effective, inexpensive local oscillator, Fessenden could not make a practical success of the heterodyne receiver. Little more than ten years later, however, electron tubes effectively filled the role of the oscillator and led to the building of functional heterodyne receivers during World War I.

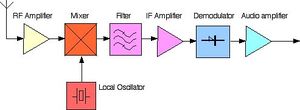

The basic scheme for radio receivers of today was patented by Lucien Lévy in 1917 (French patent or Brevet 493,660) and reduced to practice by Edwin H. Armstrong a year later. Many others--including John V. L. Hogan, Alexander Meissner, Harold J. Round, Georg von Arco, and Paul Laüt--made contributions or, in Walter Schottky's case, conceived of it independently (Deutsche Republik Patent 368937). Built on Fessenden’s earlier heterodyne technique, the essence of the superheterodyne circuit is to convert the high-frequency signal to one of intermediate frequency by heterodyning it with an oscillation generated in the receiver. The intermediate-frequency signal is then amplified before the detection and amplification that usually occurs in receivers. The superheterodyne circuit has the ability to boost weak signals significantly and makes it possible to reduce the size of antennas dramatically.

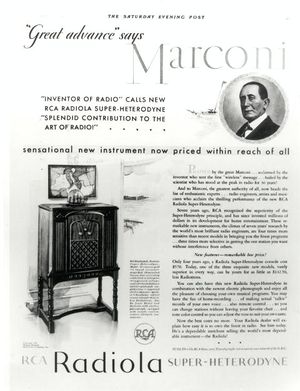

While Lévy had applied superheterodyne technology for the purpose of encoding messages during the war, Armstrong exploited it to improve reception in a radio receiver, which became commercially important as the general public in the United States and western Europe began embracing broadcast news and entertainment in the early 1920s. RCA marketed the superheterodyne beginning in March 1924. It was more sensitive than the heterodyne receiver and could be tuned by turning a single knob. Not long after RCA began licensing other manufacturers to make the superheterodyne, it became the standard circuit for radio receivers.

Armstrong went on to other achievements. In 1922, he introduced the super-regenerative circuit, which was widely used in special-purpose receivers, such as police radios, ship-to-shore radios, and radar systems. In the late 1920s and 1930s, he developed and commercialized wide-band FM technology.

Further Reading:

Alan Douglas, "Who Invented the Superheterodyne?"

Walter Schottky, "On the Origin of the Super-Heterodyne Method," Proceedings of the I.R.E. 14 (Oct. 1926)