Edison's Electric Light and Power System: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

m (Text replace - "[[[[Category" to "[[Category") |

||

| (13 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

== Edison's Electric Light and Power System<br> == | == Edison's Electric Light and Power System<br> == | ||

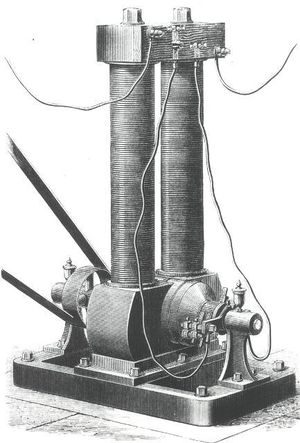

[[Image:EdisonDynamo.jpg|thumb|left|Edison's Jumbo dynamo. Courtesy: National Park Service, Edison National Historic Site.]] | |||

[[Image: | [[Image:Edison Dynamo 0185.jpg|thumb|right|Edison's Dynamo]] | ||

Edison | [[Thomas Alva Edison|Thomas Edison]]’s electric light and power installation, introduced in 1882, consisted of the large central power plant with its [[Generators|generators]] (called [[Dynamo|dynamos]]), voltage regulating devices, copper wires connecting the plant to other buildings, the wiring, switches, and fixtures in the interiors of those buildings, and the light bulbs themselves. At New York City’s [[Pearl Street Station|Pearl Street station]], where it was first installed, Edison’s team designed a huge dynamo—the largest ever built—which they nicknamed the Jumbo, and built six of them for the Pearl Street station. Each Jumbo weighed about 27 tons and had a 10-foot armature shaft and an output of 100 kilowatts. Each dynamo was driven by a steam engine, which received steam from boilers located in another part of the plant. The Pearl Street plant was designed to run up to 1,400 lamps (light bulbs inserted into fixtures) continuously, and served an area of about one square mile. | ||

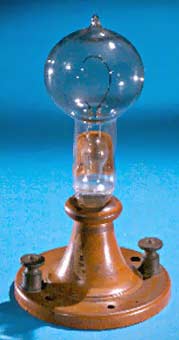

[[Image:EdisonLight.jpg|thumb|right|A lamp used at the historic 1879 Christmas Eve demonstration of the Edison Lighting System in Menlo Park, New Jersey. Courtesy: The Henry Ford Museum and Greenfield Village.]] | |||

Customers were connected to the station by thick copper wires run inside tubes called conduits. Edison believed that running wires overhead on poles might be dangerous, and doing so would put electric power in competition with the dozens of telephone and telegraph wires already darkening the New York skies. He decided to put the wires underground. The insulation for the wiring had to be carefully applied, and the streets dug up to install the conduits. At first, Edison used two copper wires to distribute electricity, but the cost of the heavy wires would contribute to the plant’s inability to make a profit for the first five years of its operation. In later installations, Edison adopted a three-wire system that allowed the use of thinner wires, which saved some of the expense of the copper. | Customers were connected to the station by thick copper wires run inside tubes called conduits. Edison believed that running wires overhead on poles might be dangerous, and doing so would put electric power in competition with the dozens of [[Telephone|telephone]] and [[Telegraph|telegraph]] wires already darkening the New York skies. He decided to put the wires underground. The insulation for the wiring had to be carefully applied, and the streets dug up to install the conduits. At first, Edison used two copper wires to distribute electricity, but the cost of the heavy wires would contribute to the plant’s inability to make a profit for the first five years of its operation. In later installations, Edison adopted a three-wire system that allowed the use of thinner wires, which saved some of the expense of the copper. | ||

[[ | From his customer’s point of view, the most important part of the system was the [[Early Light Bulbs|light bulb]]. While Edison is often remembered as the [[Edison's Incandescent Lamp|inventor of the light bulb]], there were several incandescent bulbs before his and the principle of incandescence had been known for decades. Edison did, however, achieve a long-lived, practical bulb. The problem with the earliest incandescent bulbs was that the metallic filament within the bulb would become too hot and melt. Edison found that a filament made of a loop of carbonized thread did not melt. This new design offered long life, high electrical resistance (for efficiency), and a pleasing soft light. Along with another key innovation, the improved vacuum pump, Edison was able to construct his first practical incandescent bulb in late 1879. | ||

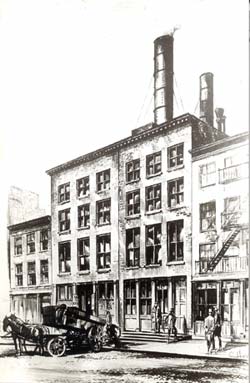

[[Image:Pearl1.jpg|thumb|left|Pearl Street Station]]With the initial Pearl Street installation a success, Edison began building systems in other places. The next two were Brockton, Massachusetts and Sunbury, Pennsylvania. The small Sunbury plant, which powered a maximum of just 400 lamps, used overhead wires on poles to save money. This pattern would continue, with large city centers served by underground conduits and smaller towns receiving the unsightly but inexpensive overhead wires. | |||

There were many technical changes in later Edison power plants. Although he continued to support the use of [[AC vs. DC|direct current (DC)]] for some years, when the new General Electric Company was formed from the Edison Electric Illuminating Company and others, it quickly adopted the more efficient alternating current (AC) technology. However, the basic system of large central stations distributing power over a broad area remained, as did the basic uses for electricity, especially the familiar light bulb. | |||

== Further Reading == | |||

For more information on the history of the electrification of New York City, Joseph Cunningham’s book, [http://www.amazon.com/New-York-Power-Joseph-Cunningham/dp/1484826515/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1383598253&sr=1-1&keywords=cunningham+new+york+powerNew York Power is available for purchase from Amazon.com] | |||

[[Category: | [[Category:Inventors]] | ||

[[Category:Power,_energy_&_industry_applications]] | |||

[[Category:Power_systems]] | |||

[[Category:Electric_power_systems]] | |||

Revision as of 14:10, 13 November 2013

Edison's Electric Light and Power System

Thomas Edison’s electric light and power installation, introduced in 1882, consisted of the large central power plant with its generators (called dynamos), voltage regulating devices, copper wires connecting the plant to other buildings, the wiring, switches, and fixtures in the interiors of those buildings, and the light bulbs themselves. At New York City’s Pearl Street station, where it was first installed, Edison’s team designed a huge dynamo—the largest ever built—which they nicknamed the Jumbo, and built six of them for the Pearl Street station. Each Jumbo weighed about 27 tons and had a 10-foot armature shaft and an output of 100 kilowatts. Each dynamo was driven by a steam engine, which received steam from boilers located in another part of the plant. The Pearl Street plant was designed to run up to 1,400 lamps (light bulbs inserted into fixtures) continuously, and served an area of about one square mile.

Customers were connected to the station by thick copper wires run inside tubes called conduits. Edison believed that running wires overhead on poles might be dangerous, and doing so would put electric power in competition with the dozens of telephone and telegraph wires already darkening the New York skies. He decided to put the wires underground. The insulation for the wiring had to be carefully applied, and the streets dug up to install the conduits. At first, Edison used two copper wires to distribute electricity, but the cost of the heavy wires would contribute to the plant’s inability to make a profit for the first five years of its operation. In later installations, Edison adopted a three-wire system that allowed the use of thinner wires, which saved some of the expense of the copper.

From his customer’s point of view, the most important part of the system was the light bulb. While Edison is often remembered as the inventor of the light bulb, there were several incandescent bulbs before his and the principle of incandescence had been known for decades. Edison did, however, achieve a long-lived, practical bulb. The problem with the earliest incandescent bulbs was that the metallic filament within the bulb would become too hot and melt. Edison found that a filament made of a loop of carbonized thread did not melt. This new design offered long life, high electrical resistance (for efficiency), and a pleasing soft light. Along with another key innovation, the improved vacuum pump, Edison was able to construct his first practical incandescent bulb in late 1879.

With the initial Pearl Street installation a success, Edison began building systems in other places. The next two were Brockton, Massachusetts and Sunbury, Pennsylvania. The small Sunbury plant, which powered a maximum of just 400 lamps, used overhead wires on poles to save money. This pattern would continue, with large city centers served by underground conduits and smaller towns receiving the unsightly but inexpensive overhead wires.

There were many technical changes in later Edison power plants. Although he continued to support the use of direct current (DC) for some years, when the new General Electric Company was formed from the Edison Electric Illuminating Company and others, it quickly adopted the more efficient alternating current (AC) technology. However, the basic system of large central stations distributing power over a broad area remained, as did the basic uses for electricity, especially the familiar light bulb.

Further Reading

For more information on the history of the electrification of New York City, Joseph Cunningham’s book, York Power is available for purchase from Amazon.com